Moses's Success at Mid-century

Edward Everett Hale, James Russell Lowell and His Friends, 155-156.

During the early years of the 1850s, Moses Dresser Phillips welcomes another son, Edward Hale Phillips, and somehow finds the time to run for, be elected to, and serve as a member of Worcester's aldermen.

While he and Charles Sampson are making many wise decisions, Moses refuses one book that he will live to regret. Since the firm has an active Southern market, and Charles Sampson's other business, in cattle and swine, is popular in Richmond and New Orleans, Phillips and Sampson decide to pass on the opportunity to publish Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin. Not long after, Stowe becomes a frequent Phillips, Sampson and Company author.

By 1853, Moses Dresser Phillips is a seasoned businessman who has learned lessons on the literary marketplace. The experience of one new house author, John Townsend Trowbridge, whose first book appears in May 1853 under the pseudonym of “Paul Creyton,” lends insights into why Phillips, Sampson and Company is so successful during the 1850s. Phillips tells Trowbridge that he wants a specific type of manuscript, “a domestic story, something that will make wholesome reading for young people and families.”

John Townsend Trowbridge My Own Story (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1903), 242

As the author later recalled, Moses also requires Trowbridge's work, [t]o be a book about this size,”-- handing me a small volume. “If you like to try your hand at something of the sort, I shall be happy to give it favorable consideration.”

Trowbridge, 242

Trowbridge compiles and quickly submits a text:

In a few days I sent Mr. Phillips the first fifty pages of the story, and went soon after to learn its fate.

‘I haven’t had time to look at your manuscript,’ he said as I took the seat to which he motioned me. That was discouraging, for, being well launched in the narrative, it was important for me to know at once if I was to go on with it. ‘I carried it home with me, to Worcester, and gave it to my wife.’ My hopes picked up a little; I thought I had rather take a woman’s opinion of it than that of the clearest-headed business man. Meanwhile I maintained a smiling serenity of manner, prepared for any fortune."

Possibly taking a cue from fellow Boston publisher John Jewett, who had heeded his own wife’s advice on Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Moses decides that he will take Charlotte’s advice on Trowbridge's book. He sends the manuscript to the stereotyper without ever reading it himself. This episode shows not only the faith Moses Phillips had in his wife’s judgment, but also the importance he sees in providing books the female public will be interested in reading and buying in a form he believes they will find attractive. Instead of asking the advice of a businessman such as firm member William Lee, he turns to a woman, one representative of an audience Phillips believes will like the book.

The efficient Phillips is extremely expedient in bringing the work from manuscript to finished product. As Trowbridge noted:

"I still endeavored to keep an unruffled demeanor, and answered, as if I had been accustomed to sample pages all my life, “Thank you, I should like to look at it.”

I was not dreaming; it was indeed a printed page of my story.

‘Then Mrs. Phillips didn’t find it so very bad?’ I said, repressing a shiver of pleasant excitement. ‘I have more here, if she would like to see it.’

‘She can read it after it is in type. The printers will want the manuscript as fast as you can furnish it, -- won’t they, Mr. Broaders? -- if we are to issue the volume this spring, which we think will be a good time for it.’

This was a bewildering surprise to me, but I merely remarked that I had expected to revise the manuscript carefully before it went to the printers.

‘What revision you find necessary can be done in the proofs,’ said Mr. Phillips, decisively, handing my second batch of copy to Mr. Broaders, with hardly a glance at it.

So it chanced that the story passed into type about as fast as it was written, with all its imperfections; and I hadn’t the heart to do much to it in the proofs. In about three weeks it was ready for the binders, and it was published in that month of May, 1853.

Its success was immediate, and far exceeded my expectations, for the little volume seemed to me exceedingly faulty, as soon as it had gone irrevocably out of my hands. The critics were kind to it; people of the most opposed sectarian views united in accepting Father Brighthopes as an embodiment of practical Christianity--that religion of the heart, which is no more a part of any creed than a living spring is part of the strata through which its waters gush; and I was soon gratified and humbled by hearing how he had affected many lives--more, I feared, than he had affected mine! Readers of the book generally conceived of the author as himself a venerable clergyman; and some who sought his acquaintance on account of it expressed incredulous surprise on finding him hardly more than a boy.

Edward R. Broaders, the stereotyper, serves as an important member of the Phillips assembly line. When the book is actually bound in cloth, it is, indeed, in the small 18mo format Phillips, Sampson and Company and other firms often used for women’s and children’s fiction and cost fifty cents. Trowbridge, the author of Father Brighthopes, finds that he has been able to write a book that can please a diverse religious audience, despite the time constraints placed on completing the work.

Phillips, Sampson and Company is now one of the most important firms in the United States. During 1854, the thriving Moses and Charles open a grand new store at 13 Winter Street in Boston.

The firm’s most popular authors are Emerson and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Although they promote new American authors, such as John Townsend Trowbridge and Ellen Louise Chandler, P, S & Co. also continues to publish many books by British and Scottish authors.

At this point, the firm’s major genres are juvenile literature, poetry, textbooks, history, biography, and fiction.

Through his strategy of "paying money for glory," Moses is able to attract top notch authors.

Little, Brown and Co., One Hundred Years of Publishing, 1837-1937 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1937), 5-6, quoted in Raymond L. Kilgour, Lee and Shepard: Publishers for the People (s. n., The Shoe String Press, Inc., 1954),14.

One popular authar he steals away from the Harpers in the mid-1850s is the historian William Hickling Prescott.

Prescott has good luck with his publications during 1856. In June, he writes to a friend that “[m]y books have gone off merrily. My publishers account to me for thirty thousand volumes of the old and the new works, sold in the last six months. As they are all of the large 8vo size, this shows that our public loves good books -- don’t you think so?”

William Hickling Prescott to Lady Mary Lyell, 9 June, 1856. C. Harvey Gardiner, ed. The Papers of William Hickling Prescott (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1964), 361.

Information from the advertisement for Prescott's books within the 1856 firm catalogue further explains the financial gains from the author's publications:

MR. PRESCOTT'S works are printed upon fine paper, with large, clear type, and bound in all styles. Price, in muslin, $2 per volume; in sheep, $2.50; half calf, or half antique, $3; full calf, or antique, $4.

"PRESCOTT'S HISTORICAL WORKS," Phillips, Sampson and Company catalogue, 1856, included within William Phillips, The Conquest of Kansas by Missouri and her Allies. Boston: Phillips, Sampson and Company, 1856.

Since each of his works has at least two volumes, the firm makes between four and eight dollars per title for the two volume editions, and between six and twelve dollars per title for those titles with three volumes. Moses Dresser Phillips's ability to recruit William Hickling certainly profits his publishing firm. Although Prescott believes that the sale of 8vo books indicates a public interest in "good books," Moses Dresser Phillips surely looks forward to the day when a larger "public" can afford to purchase 12mo versions in the experiment he calls the "Post-Octavo Scheme."

The firm's promotion of Prescott's books also lends insight into what the publishers believe to be popular with and important to the public:

PRESCOTT'S

HISTORICAL WORKS.

ATTRACTIVE AS ROMANCES!

IN all the qualities that distinguish the great historian, MR. PRESCOTT stands preeminent. His materials have been collected with great labor and research, and his style of narration is clear, flowing, and elegant. The reader has never to wander, perplexed, through accumulations of ill-arranged matter; perfect order is evident in all these works. The interest never flags; for the author has the happy faculty of seizing upon salient points, and grouping even minute details with picturesque effect.

"PRESCOTT'S HISTORICAL WORKS," Phillips, Sampson and Company catalogue, 1856, included within William Phillips, The Conquest of Kansas by Missouri and her Allies. Boston: Phillips, Sampson and Company, 1856.

Phillips, Sampson and Company, cognizant of the female market, attempts to tie the histories to the romance category. The Boston firm also promotes the books by noting the author’s clarity of style, a factor the publishers know is important in the lives of its audience.

To shorten his commute to work, and to be closer to Edward Everett Hale's new parish in Boston, Moses, Charlotte, and his family move to Brookline Village. Now he lives just four miles away from the Winter Street store.

Being closer to Boston also facilitates Moses’s ability to participate in political activities. In late June, shortly after the Republican Convention in Philadelphia, he attends a Faneuil Hall meeting of Boston area Republicans “to ratify the nominations of John C. Fremont and William L. Dayton.” As he had in Worcester, Moses takes a leadership role and is elected as one of twelve Vice-Presidents of the local Republican Party.

"Great Republican Ratification Meeting in Faneuil Hall,” Liberator, 27 June, 1856, 103

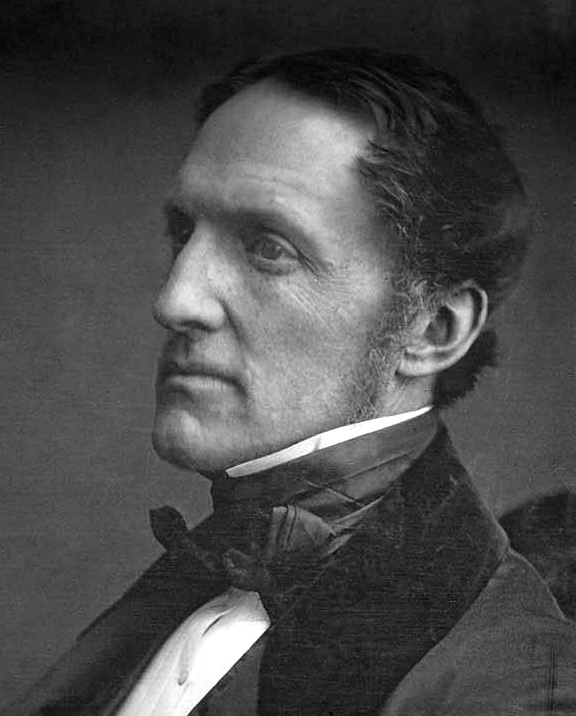

Ralph Waldo Emerson, another important author, brings forth English Traits and Miscellanies: Embracing Nature, Addresses, and Lectures. Phillips, Sampson and Company also reprints his Representative Men, issues a new edition of Essays, First Series, and presents the public with a fifth edition of Poems.

Emerson also continues to promote the Boston firm to his own friends and colleagues. In response to Thomas Carlyle’s request for an American publisher for his collected works, Emerson suggests Phillips, Sampson and Company:

Concord, August 22, 1856

Dear Carlyle: -- Here is the proposal in full of Phillips, Sampson & Co., in reply to my explanation of your design. It looks fair and fruitful to me, though I am a bad judge. The men Phillips and Sampson are well esteemed here, have great confidence in themselves (which always goes far with me), and I believe will keep their word as well as any of their kind, though in all my experience of mortal booksellers there are some unlooked-for deductions in the last result. I have neither a right nor a wish to throw any doubt on these particular booksellers, who mean the best. I hasten to send the letter, before yet any steamer from Liverpool can bring me any growl of wrath from my dear lion. Stifle the roar, and let me do penance by appointing me to negotiations and mediations with P, S & Co. and the printers, which I will gladly and faithfully execute.

Ralph Waldo Emerson to Thomas Carlyle, August 22, 1856, The Correspondence of Emerson and Carlyle. Edited by Joseph Slater. (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1964):512-513.

Through Emerson's letter to Carlyle, we learn that the Boston firm has earned the respect of the American public and press, and of one of its most important authors. Since he understands Phillips's persuasive ability, Emerson urges the British author to let him handle the arrangements.

At the end of 1856, when he is profiting from Prescott's histories, Emerson's English Traits, Harriet Beecher Stowe's widely anticipated antislavery novel Dred, Epes Sargent's textbooks, and the works of many other authors he knows are popular with the public, Moses Dresser Phillips's prospects look bright.

Phillips, Sampson and Company is an established name within the publishing profession and in the minds of consumers. Phillips utilizes what he has learned from his mentors and his experience with the public, listening to voices and also spreading his own worldview through the choices of publications, authors and forms. By offering products with quality paper and type, at reasonable prices, Phillips, Sampson and Company wisely makes its books accessible to a wide audience. The publishers use broadsides, newspaper and periodical advertisements, firm catalogues, known names, and the word of mouth, to familiarize the public with the house’s identity and products.