October 22 - October 28

Women of the Week

Emily Huntington Miller, an author and educator, Mary J. Scarlett Dixon, a physician, Emma McAvoy, a lecturer, Helen Augusta Blanchard, an inventor, and Anna Elizabeth Dickinson, an orator, author, playwright, actor, reformer, and philanthropist, are this week's Women of the Week.

-

To learn about them by viewing their items, please click on their images.

-

To read their biographical sketches in A Woman of the Century, please click on the highlighted page numbers to the left of their images.

Emily Huntington Miller was born in Brooklyn, Connecticut, on October 22, 1833. She was a writer from a young age, and she graduated from Oberlin College.

In 1860, Emily married John E. Miller, whose career achievements included being a principal, a professor, and the publisher of Little Corporal, which later merged with St. Nicholas. Emily, John, and their children lived in Granville, Illinois, Plainfield, Illinois, Evanston, Illinois, and St. Paul, Minnesota. Emily wrote for and edited Little Corporal, and she contributed to newspapers and periodicals such as Harper's Magazine, The Independent, and Our Young Folks. A prolific author, Emily penned several books, including The Royal Road to Fortune (1869), Hang Up the Baby's Stocking (1870), The Parish of Fair Haven (1876), What Tommy Did (1876), The Bears' Den (1877), Captain Fritz: His Friends and Adventures (1877), Summer Days at Kirkwood (1877), A Year at Riverside Farm (1877), and Little Neighbors (1879). Also a lyricist, she wrote the words for Only Four! Song and Chorus (1868), by George F. Root. In addition to her literary career, she was involved with missionary and Sunday school work for the Methodist Episcopal Church. From its start in 1874, Emily was active in the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle. She also was an early temperance advocate.

After John's death in 1882, Emily continued her literary activity. She wrote for various periodicals, including Atlantic Monthly and Ladies' Home Journal, and published books of prose, poetry, and lyrics, including Home Talks about the Word: For Mothers and Children (1894), Songs from the Nest (1894), From Avalon, and Other Poems (1896), and An Offering of Thanks (1899).

Emily became president of the Woman's College of Northwestern University in 1891, and served as president of the Chautauqua Woman's Club for several years.

She passed away on November 2, 1913.

Mary J. Scarlett Dixon was born in Robeson, Berks County, Pennsylvania, on October 23, 1822. She grew up in a Quaker family that became very involved in the Anti-Slavery cause. Having lost both parents by the age of sixteen, Mary was very interested in medicine. After pursuing a teaching career, she entered the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1855. When Mary graduated in 1857, she continued to take classes, worked with poor patients, and delivered lectures on medical topics.

Beginning in 1859, Mary taught at her alma mater and held the title of Professor of Anatomy. Eventually, she established a successful practice in Philadelphia and changed her position to Professor of Anatomy and Histology. Mary's colleagues included Rachel Bodley, Emeline H. Cleveland, and Ann Preston. On March 16, 1867, Mary gave the valedictory address at the graduation ceremony. Her address, which was printed in The Evening Telegraph that evening, included wise advice for both future physicians and all women.

After she married G. Washington Dixon on May 8, 1873, when she was fifty years old, Mary continued to teach and practice medicine. In addition to her medical practice and personal life, Mary advocated for peace reform. When she was named a member of the Executive Board of the Pennsylvania Peace Society in 1876, she worked with Lucretia Mott and others for this cause.

In 1881, Mary left the faculty of the school that had been renamed The Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, and an article from October of 1885 in the Richmond Dispatch referred to Mary as "professor emeritus...." Unfortunately, Mary suffered from glaucoma. By 1886, she also needed to curtail her practice.

Mary passed away in Philadelphia on January 28, 1900, and is buried in that city's Fair Hill Burial Ground.

Emma McAvoy was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on October 23, 1841. Author and lecturer are the occupations listed at the beginning of her A Woman of the Century profile, but Miss McAvoy's career included other professions.

Like many women of her time, this daughter of an Irish immigrant began her career as a teacher. In April of 1859, Emma was appointed as a teacher in Cincinnati's Third District with a salary of twenty dollars. Her salary may have been low because she was hired in April, since she is listed as having earned three hundred dollars the next year. Later, Emma served as a principal in Kansas City, Missouri.

Upon her return to Cincinnati, Emma began to deliver lectures. Her A Woman of the Century profile notes: "She was one of the first women who presented parlor lectures on literature in the West" (481). On February 11, 1879, The Cincinnati Daily Star advertised one of her upcoming lectures: "Miss Emma McAvoy will deliver, at College Hall, on the evening of the 28th of February, an evening lecture on the subject, 'The Ode and Errors in Conversation.'" Other lectures over the next two years were on "Sonnet, with Hints for Improvement in Conversation," and "The World's Conversationalists."

As a popular figure on the lecture circuit, Emma often received praise in the press. For example, a week before her 1884 speech in Omaha, Nebraska, The Omaha Daily Bee advertised:

"On next Monday evening, November 24th, Miss Emma McAvoy will lecture on the subject, 'Hints for Improvement in Conversation.' The lady has just delivered four lectures in Denver, and is said to be a pleasing speaker."

She also gave "an able address well delivered" on "Books" in Denver, Colorado, and a "well attended and thoroughly enjoyed" lecture on "Conversation" in Maysville, Kentucky, during 1896. Emma was still lecturing by 1900, when she lived in Cincinnati with her sister Mary.

Emma passed away on February 4, 1919, and is buried in Cincinnati's Spring Grove Cemetery.

Inventor Helen Augusta Blanchard was born in Portland, Maine on October 25, 1840. She was the daughter of a wealthy shipowner and businessman. When her father's business failed and he eventually died in 1866, Helen took to patent development and monetized her inventions. Over the course of about 40 years, Helen patented 28 inventions including the zig-zag stitch sewing machine. In 1876, she founded the successful Blanchard Over-Seam Company of Philadelphia.

The May 1, 1913 Washington Evening Star noted: "One of the most important of the patents granted during the centennial year was an overseaming machine which has become invaluable to manufacturers of knitted fabrics and of various articles of ready-made clothing. It was invented by Miss Helen Augusta Blanchard, who established a large company in Philadelphia."

After living in Philadelphia, she moved to New York City. She passed away in Providence, Rhode Island on January 22, 1922, and was buried in her home of Portland, Maine.

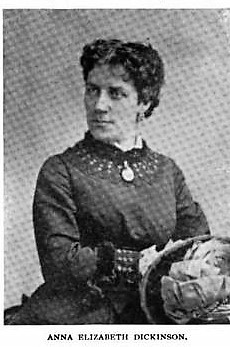

DICKINSON, Mrs. Anna Elizabeth

October 28, 1842

orator, author, playwright, actor, reformer, philanthropist

Philadelphia, PA

Anna Elizabeth Dickinson was born on October 28, 1842, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her father passed away in 1844, when Anna was two years old. She went to the Friends' Free School, studied hard, and read constantly.

By the age of fifteen, Anna had written her first article on slavery and had spoken at a meeting for the Anti-Slavery movement. She taught in Berks County, Pennsylvania before becoming a professional lecturer. Anna traveled around New England delivering addresses about slavery, temperance, and politics. When Anna gave an address in Washington, D.C. during the early 1860s, she donated all of the proceeds from the event to the Freedmen's Relief Society.

Also a writer, Anna published the novel What Answer? in 1868. Next, she decided to pursue playwriting and acting. Anna wrote a play called "A Crown of Thorns" and made her debut on the stage. When this career path ultimately failed, she decided to return to lecturing and continued to write plays.

Anna died in Goshen, New York when she was eighty-nine. She is buried at Slate Hill Cemetery, Goshen, New York.